By MSW@USC Staff, March 15, 2018

Living under the perceived threat of detention and deportation is having harmful mental health effects on undocumented immigrants and their families, according to Dr. Concepcion Barrio, associate professor at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work.

“It just creates an air of constant fear and being on edge,” she said. “They are afraid to go outside, to look out of place in a certain neighborhood, and to go out and seek a job.”

While the total number of deportations has continued to decrease under President Trump due to backlogged immigration courts and fewer people crossing the border, arrests of undocumented immigrants by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents rose about 43 percent in 2017, according to a report from The Washington Post External link . Between January and September, ICE arrested more than 28,000 noncriminal immigration violators — three times the number during the same period the previous year.

And children, who are undocumented or who have parents or caretakers who are undocumented, can be especially vulnerable to the mental health challenges of family separation, resulting in a number of harmful behavioral changes that can interrupt important childhood development.

“Imagine your family ripped apart. That’s going to have reverberations across family members for years to come,” added Dr. Barrio.

Although the current administration insists that it is prioritizing the removal of criminals, immigration advocates point to the growing number of arrests of noncriminal undocumented immigrants as a sign that those priorities no longer exist.

The Impact of Stress on Children

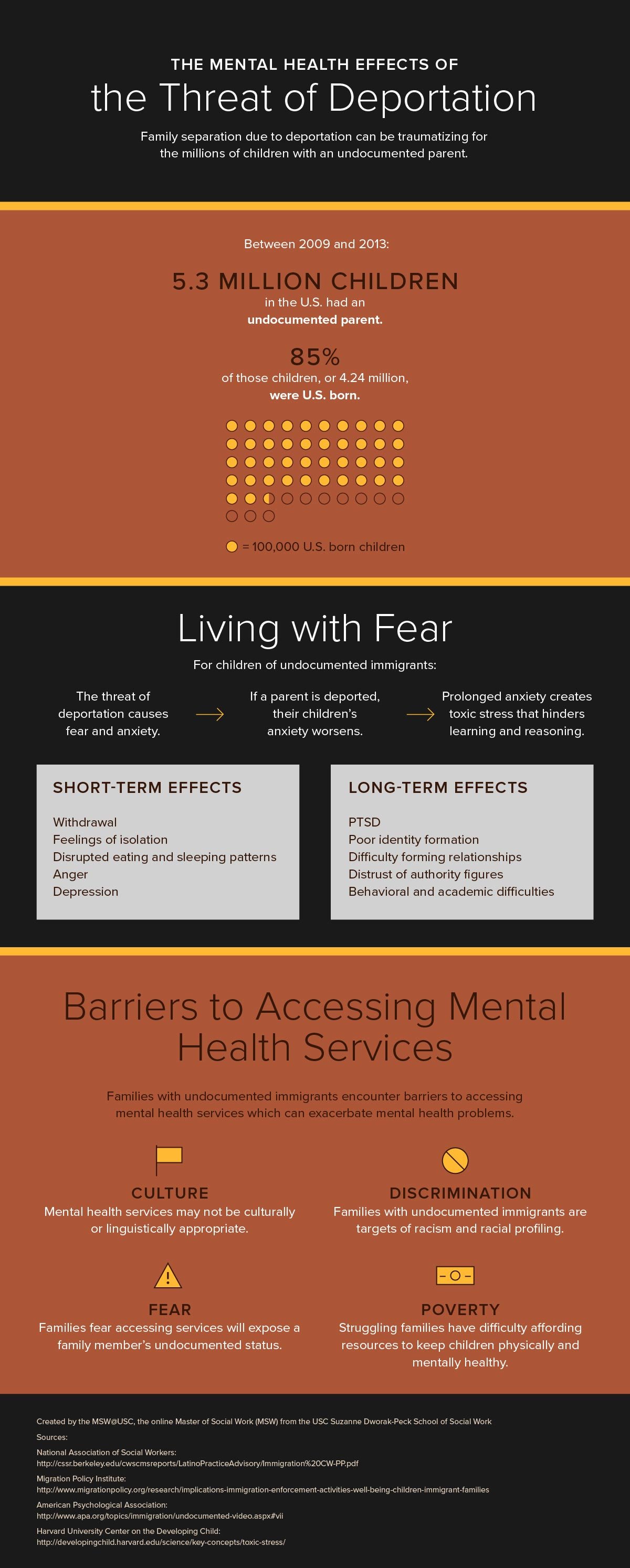

Among the noncriminal immigration violators are undocumented immigrants with children. From 2009-2013, the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) estimates that more than 5 million children under 18 — 4.1 million of which were U.S. citizens — lived with an undocumented parent.

Information on the number of children whose parents are deported is scarce. However, MPI estimates that as many as 500,000 External link deportees between 2009 and 2013 may have been parents, affecting roughly the same number of U.S.-citizen children.

Regardless of their documentation status, children with undocumented family members are not shielded from living under the constant fear that their loved ones may be taken from them without warning.

“When children are traumatized, that trauma is a pivotal moment in their life that’s going to define how they see themselves — how they identify as a person of color, as an American, as a Mexican American, as a young person, as a student,” said Dr. Barrio.

“Just knowing that your parents are undocumented, even if they are not in the process of deportation, produces a state of persistent stress which has both physical, as well as psychological and emotional consequences,” said Dr. Barrio.

Children who live in a heightened or prolonged state of stress, sometimes called toxic stress, in their formative years without necessary adult care and intervention can overload External link their stress response system, physically affecting brain functions such as learning and reasoning.

“The child’s brain is still developing up to the age of 22, so they are very vulnerable to the biological processes that affect the brain during development,” said Barrio.

While she noted that academic performance tends to be the most measurable way to show the impact of this stress, she added that many families who she has encountered facing these situations also report mental health disorders.

Many children with a detained or deported parent experience depression, anger and social isolation that can manifest in erratic physical and mental health behaviors External link , such as refusal to eat, self-harm, poor sleep, and chronic head and stomach pain, according to MPI External link . A survey conducted by Human Impact Partners External link echoed these findings, reporting that youth with one or more undocumented parents often reported feeling withdrawn and angry — 29 percent and 46 percent, respectively — due to threats of detention or deportation.

The long-term impact of the trauma associated with deportation of a parent can also result in severe health and emotional issues for children like post-traumatic stress disorder, poor identity formation, difficulty forming relationships, distrust of institutions and authority figures, and behavioral and academic difficulties at school, notes the American Psychological Association. External link (APA).

“When children are traumatized, that trauma is a pivotal moment in their life that’s going to define how they see themselves — how they identify as a person of color, as an American, as a Mexican American, as a young person, as a student,” said Dr. Barrio.

In addition to these individual consequences, deportation can also cause deterioration of crucial familial relationships and a dissolution of the family network External link , which sometimes forces children into the foster care system. Often, families with undocumented immigrants must navigate these obstacles while also encountering discrimination External link , racism and racial profiling.

Creating a Safe Space

Providing the necessary mental health interventions to undocumented communities can be a challenge for social workers. Many families are fearful External link of accessing critical mental health services due to the risk of exposing a family member as undocumented. Additionally, Latinos and immigrants attach a social stigma to mental health challenges.

“The culture is kind of a double-edged sword. It’s protective in that you’re insulated by a culture that is generally collectivistic and family-oriented, where faith and hope are huge protective factors,” said Barrio. “But on the other side of it, there is such a misunderstanding and a lack of adequate information about mental health and mental illness that it interferes with timely help-seeking and being open to receiving help.”

To better address the needs of families facing mental health challenges, Dr. Barrio and her colleague Dr. Paula Helu-Brown partnered with the Mexican Consulate of Los Angeles to create a first-of-its-kind mental health counseling program which offers free services on site for clients regardless of immigration status. USC has now developed a smaller program at the Consulate General of El Salvador in Los Angeles.

“Families facing stress and anxiety related to their documentation status can learn to cope by relying on each other.”

“We are hoping to also create a culture where people feel comfortable in utilizing mental health services,” said Dr. Helu-Brown, who serves as a clinical coordinator and community liaison for the program.

Participants in the programs meet with a USC intern, under the supervision of a licensed social worker, who is trained to conduct speedy mental health evaluations. If a case is manageable, interns provide brief cognitive behavioral therapy where they focus on teaching coping skills and teaching adults how to deal with anxiety and depression.

If a person has more severe mental health conditions, interns will refer that individual to a community provider for a higher level of care. USC is also planning to provide telehealth treatment for children in 2018.

Dr. Helu-Brown hopes to see social workers implement lessons learned from their experience over the past year by working with consulates, where programs are available for those facing deportation, and community centers to support immigrants.

“[These programs] are trying to provide job opportunities. They are trying to provide health related services; school for their children; legal support. That can help ease some of that anxiety,” Dr. Helu-Brown said.

But she also noted that families facing stress and anxiety related to their documentation status can learn to cope by relying on each other.

“What I tell them is to always try to draw on the support they get from their community,” she said. “It is important to stay together and to support each other. If they are religious or spiritual, draw strength and hope from that. And understand how politics are kind of like an ebb and flow. Things might be a certain way now, but hopefully as time moves on and people learn from experiences things might be a little different.”

MPI and the Urban Institute offer a comprehensive list External link of recommendations for health and human services providers working with immigrant families and children based on successful interventions in a number of cities, including:

Relying on organizations such as schools and universities, as well as community-based, faith-based and advocacy organizations to fill in service gaps. For example, the list notes that staff at schools in Los Angeles were able to incorporate community mental health programs into their services, while high schools in Chicago hired counselors specifically for immigration-related issues. Immigrant advocacy organizations across the country have also helped to establish support groups for families impacted by deportation and have rallied to provide short-term financial support to mixed-status families.

Strengthening trust in service providers by working with organizations with deep ties to communities.Families with undocumented immigrants are more likely to trust organizations that have been proven advocates for their communities, share the same religious affiliations, and employ staff that have the same background as the communities that they serve.

Developing an understanding of the various immigration statuses and connecting with immigration specialists for their expertise in order to help assess relief options. For example, the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) offers state social workers training sessions on immigration issues at an annual conference and created a handbook for social workers that offers explanation on immigration statuses and how that can affect child welfare.

Coordinating with child welfare agencies, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and foreign consulates to ensure that children’s rights are protected, make certain that parents maintain contact with children, and plan for family reunification. For example, the Illinois DCFS has successfully worked with the Mexican consulate to locate parents after deportation and conduct home visits in Mexico to ensure that children who are reunited with their parents are in a safe and secure setting.

Citation for this content: The MSW@USC, “The Online master of social work program at the University of Southern California.”

Source: https://msw.usc.edu/mswusc-blog/facing-the-fear-of-deportation/